By Indira A.R. Lakshmanan, Globe Staff | August 27, 2006

CARACAS -- When a Venezuelan crime drama broke box-office records here last year, drawing critical acclaim and a cult following in the ghettos where it was filmed, the young director hoped the movie would spark a debate on how to address poverty, violence, and class divisions.

CARACAS -- When a Venezuelan crime drama broke box-office records here last year, drawing critical acclaim and a cult following in the ghettos where it was filmed, the young director hoped the movie would spark a debate on how to address poverty, violence, and class divisions. Instead, the nation's most successful home-grown film ever, which depicted the kidnapping of a rich, cocaine-snorting couple by barrio gangsters, ignited a furious backlash from the government.

Vice President José Vicente Rangel has denounced the movie, loosely based on the real-life kidnapping of the director, as "a falsification of the truth with no artistic value."

The director is being sued for "vilifying" President Hugo Chávez, though the president never appears in the film, nor is he mentioned.

In January, the hosts of a government television program accused the Jewish filmmaker of being part of a "Zionist conspiracy against Chávez." The next morning, the president angrily called for laws to block the production of films that "denigrate our revolution."

Hours later, the 28-year-old director, Jonathan Jakubowicz, fled the country, fearing for his life.

The controversy over "Secuestro Express" ("Express Kidnapping") is one chapter in a bitter tug of war over culture and image in Chávez's Venezuela.

Critics say the government is obsessed with promoting a perfect picture of life under Chávez, sponsoring art that feeds his personality cult and glorifies his populist revolution. Artists who criticize Chávez or portray anything negative about contemporary Venezuela say they are condemned or sidelined.

In a telephone interview from Hollywood, where he took refuge, Jakubowicz said the message of his film was that rich and poor need to work together to solve the country's problems -- a notion that, according to him, threatens a government that prefers to perpetuate rather than resolve class struggle.

"My movie was never against the government," he insisted. "But those who speak about the reality of the country" are silenced. The authorities "want to create an artificial reality like the Soviets did, where you can only talk about the problems of the past. If you talk about the present, it has to be perfect."

Culture Minister Francisco "Farruco" Sesto, an architect and writer, dismissed such assertions as "a total lie. There is absolute liberty of expression," he declared.

In fact, Chávez has made culture less elitist and more inclusive, and has encouraged Venezuelan artists to step out of the shadow of US cultural domination, he said.

The president's supporters cite the following:

In early June, Chávez inaugurated a state-of-the-art film studio built by the government, praising it as a weapon in Venezuela's "artillery" against the "cultural dictatorship" of Hollywood. The studio's goal is to help Venezuelans produce 12 documentaries, 12 feature films, and two television series a month, with generous government financing.

Chávez founded the Ministry of Culture, which houses numerous literary presses, including one devoted to publishing a book a day. Poetry festivals have been opened to all comers. And the nation's art museums held "mega-exhibitions" last year to which any citizen could submit work to be displayed next to those of famous living artists.

A media "social responsibility" law passed last year requires that at least half the music played by radio stations be Venezuelan, and that half of that be traditional folk music.

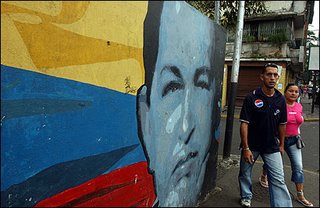

The president's foes, however, argue that Chávez's cultural initiatives are all about promoting Chávez and his nationalistic revolution. Gracing highways, avenues, and community centers are giant murals, often commissioned by pro-Chávez local governments, that depict the president in grand proportions alongside Latin revolutionaries and Venezuela's independence leaders.

State funding is impossible for projects openly critical of Chávez, some artists say, adding that even private firms -- fearful of government backlash -- won't sponsor controversial theater or art works.

Chávez loyalists insist the government is supporting new artists from all walks of life, and that the only ones complaining are the privileged elite who held a stranglehold on high culture before Chávez took power.

"Cultural space has opened as never before. There are Afro-Venezuelan and indigenous acts in national concert halls," said painter Régulo Pérez, 76, whose collages -- including several works attacking US militarism -- were recently showcased at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas. ``There's a great renaissance going on . . . It's a cultural transformation."

But art historian Beatriz Sogbe scoffed at the idea that cultural expression is now more democratic. "A real revolution elevates people's thought. This is just cultural populism, the idea that everyone should lower their level," she said .

Decrying acts of vandalism in recent years of Venezuelan sculptures and paintings in the custody of local municipalities, she compared Venezuela under Chávez to China under Mao Zedong, where communist authorities allowed student radicals to destroy classic works of art and literature.

Disparaging the museum mega-exhibitions, she called it an "offense" to display the work of any citizen next to masterpieces. Chávez, she said, has removed standards .

But Sesto, the culture minister, bristled at Sogbe's criticisms, saying that isolated cases of vandalism were crimes, not state- sanctioned attacks on art. The government is prosecuting militants who knocked down a Christopher Columbus statue as a political statement, he added.

As for the mega-exhibitions, Sesto said, "it was a gesture of inclusion." It's not that everyone is getting to show his or her work in museums all the time, she said.

Lorena Almarza, president of the new $24 million Cinema City studio complex, said that by funding more than 200 documentaries and 50 television series last year, the "state is promoting . . . projects of national interest . . . If that's nationalistic, then yes, we are cultural nationalists."

Hollywood has long dominated offerings at local theaters, and Cinema City will lend its resources to projects reflecting Venezuelan life and break negative stereotypes of Latinos in US movies, she said, and the revolution underway will help "democratize the cultural assets and services of the country."

Music is an area where a Chávez-inspired law has already affected both the creation and enjoyment of an art form. With national music quotas, stations that previously adhered to a jazz, classical, or reggae format, for example, can no longer do so.

Yet many musicians, even those who dislike what they perceive as imposed nationalism, applaud giving airplay to Venezuelan artists who couldn't otherwise compete with foreign acts. Unusual hybrids have arisen to accommodate the law -- such as hip-hop sampling folk ballads.

"I think the intention was to decrease the amount of American music [played] . . . and that has given a chance to new musicians," said Ricardo Nuñez, 25, an electronic musician.

Others see it as an insidious intrusion by the state into something as personal as musical taste. "We're listening to the same music all the time now," said Alejandra Otero, 23, a former radio disc jockey. "Little by little, the state is generating more and more restrictions on liberty."

Several artists said they or their colleagues were exercising self-censorship to avoid being excluded from exhibitions or singled out for public attack.

Many cite the case of digital video artist Pedro Morales, whose work "City Rooms" (www.cityrooms.net) was chosen to represent Venezuela at the prestigious Venice Biennial in 2003.

But when the Ministry of Culture realized the work included images of demonstrations that threw the country into turmoil in 2002 and 2003, and ridiculed a speech by the president, their invitation to Morales to represent the country was withdrawn, raising cries of censorship from Morales and some curators.

Being stripped of an honor is not the same as censorship, the culture minister noted, saying he could not imagine any government sending a work of art that is hostile to its leader as a representative of the nation.

"There are certain things that no state would accept," Sesto said.

Feather's commentary about this article:

In the matter of the arts, Chavismo cannot deny its nature. It's all about mural sized pictures of Chavez and its ministers picking babies, kissing old ladies and hugging brown skinned children with big smiles on their faces, surrounded with a landscape full of flowers and butterflies á la Mao.

As we just read, artists who criticize Chavez are not sponsored by the government. And on the other hand, some artist who are in agreement witht the revolution are favored by it. But someone with no art education, should ask, and why should they sponsor art who criticize them? And the answer is very simple, art cannot have any type of censorship, either by the society, by their religions, by their morals, because it can be consider it obcene or because it can offend sensibilities of the government. Point in case and to be fair, not to say that Chavismo is the only government who censor arts, I think about John Ascroft covering the private parts of the statues of the Great Hall at the US Justice dept. They didn't last too long covered though. Or Guiliani, a devote catholic like myself, closing a show in the Brooklyn Museum of Art about since it portraited the Virgin Mary made in elephant poop by an african artist whose name I cannot recall. I mean, if I don't like it, I won't go, that's all. Just imagine some Venezuelan artist decide to make Chavez's portrait in poop (hint) and the government censor it. I can see the regime closing the exhibit for no reason, and Chavez is not even closer in importance to the Mother of God for many. Not all artist made good art, and there's the eternal question of what is art. But an artist never should be censored. Some exhibits who can be seen as offensive by many or not understood by children can be show discretely. Remeber the way nazism and communism have censor arts during time.

But going back to the chavismo, they don't care about obcene censorship, you know covering some statue's johnson. One must think about the difference of covering some statue's private parts or censor an artist or a movie because it's not in agreement with a political revolución.

Also, one must note the illegal electoral campaign that Mr. Chavez has decided to set, stepping over electoral law. Bruni has documented this images pretty well, they are not art, but it kind of fits in what this article is talking about. Their way or the highway. Draw your own conclusions.

No comments:

Post a Comment